Why white evangelicals have an extremism problem

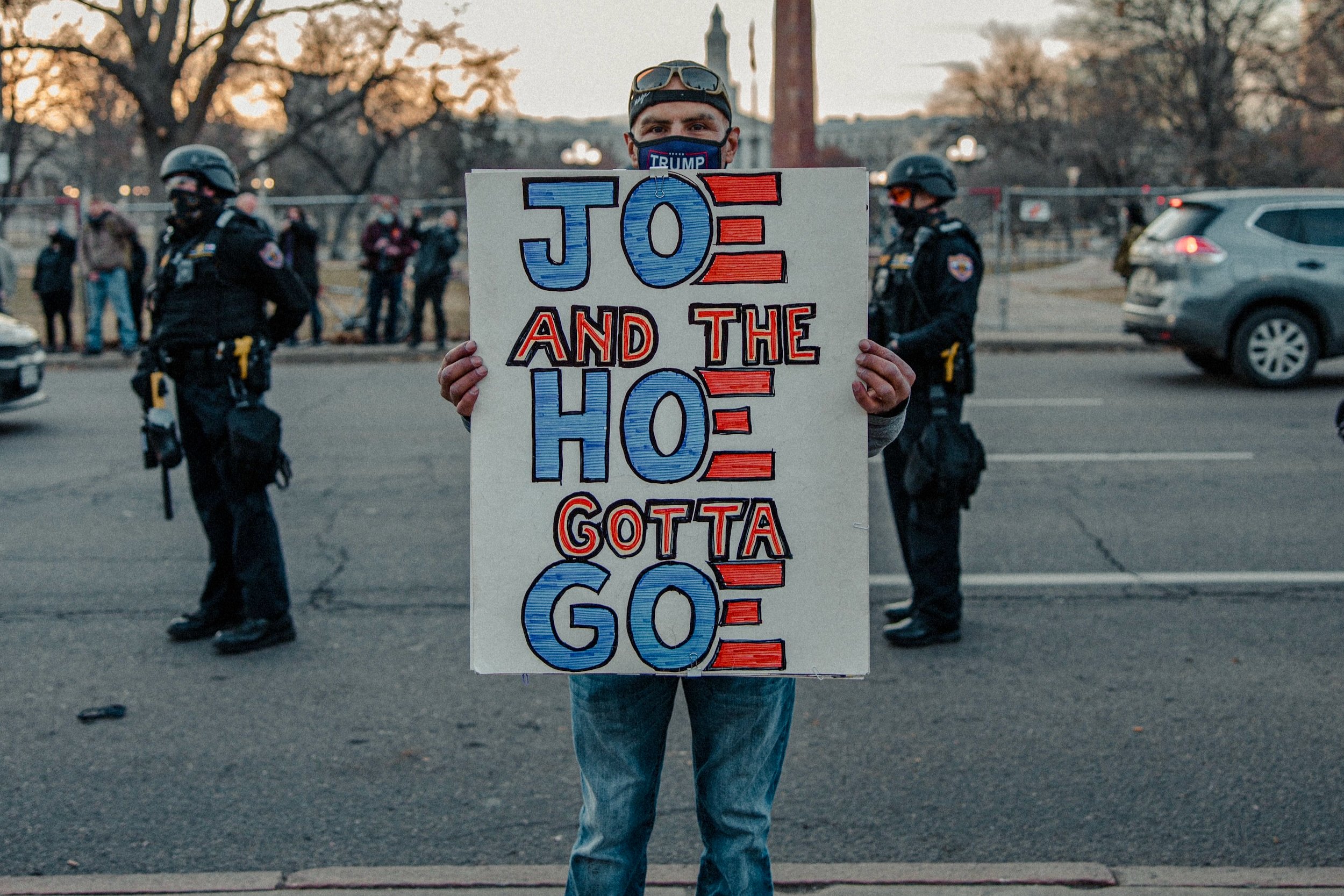

Watching the January 6 coup attempt at the U.S. Capitol, I was upset — but completely unsurprised — to see Jesus Saves signs amidst the Trump and Confederate flags, a gallows, and makeshift weapons being wielded against outnumbered Capitol police.

I was shocked because, well, it was shocking. Having walked the halls of the Capitol complex many times, it was heartbreaking to see images of specific places I have been being desecrated. Knowing that many of the devoted Capitol police officers and kind Congressional staffers I have met over the years were now in danger was even more concerning.

I was not surprised because I’ve been in various forms of evangelicalism for most of my life. As I write this, I attend a church with the word evangelical in the title, although I haven’t identified as an evangelical for years. I’m still a Christian. At some point though, lived experience paired with the teachings of Jesus made me realize that evangelical is too loaded of a term and experience. It made loving God and my neighbors way harder than it should be.

There are certainly many kind evangelicals. I count some of them as friends. They give generously, go out of their way to help others, and have a genuine desire to follow the teachings of Jesus. Despite how they are defined in the media, their political leanings range the spectrum, and they get along with people who don’t agree with them just fine. They accomplish this by adhering closely to Mark 12:28–31:

“And one of the scribes came up and heard them disputing with one another, and seeing that he answered them well, asked him, “Which commandment is the most important of all?” Jesus answered, “The most important is, ‘Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one. And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength.’ The second is this: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ There is no other commandment greater than these.”

Many of these evangelicals were rightfully outraged by what happened in our nation’s Capitol. They usually keep their head down, serving quietly and humbly, but this time they forcefully spoke out. Good for them.

Then there are those evangelicals —cultural white evangelicals— who have fallen prey to conspiracy theory, traffic in far-right ideology, and are consumed in their own political idolatry. They are the die-hard Trump supporters that the New York Times and other media outlets obsessively cover for reasons beyond understanding. The QAnon conspiracy theory is capturing more and more of them. Abusive and angry, they loudly proclaim their heresy everywhere they go, even during the violent insurrection at the Capitol. They are white Christian nationalists, not followers of Jesus.

That’s usually where the landscape portrait of today’s evangelicalism ends, but this is too black and white. It makes for great national theater, often pitched as a civil war in churches. But it is completely unhelpful in actually rooting out the problems in white American evangelicalism.

Yes, these two types of evangelicals exist and operate in predictable ways with predictable results, but there is another type of evangelical we rarely talk about. And we really need to understand who they are.

Meet the Absolutist White Evangelical

If you are in an evangelical church, odds are you know this person. They are very different from the mob who stormed the Capitol; however, they have been actively building up a white evangelical culture that has contributed to the increasing political polarization and the us vs. them mentality that pervades American life today.

Specifics, please?

They often speak about what they are against, but rarely about what they stand for. They believe older male leadership in the Church is never to be questioned, even when wrongdoing is as clear as day, and they enforce that belief.

They decry cancel culture and socialism, even though they unknowingly engage in both practices. They claim identity politics is evil, not understanding that all politics stems from identity and that they are willing participants in their own way.

Many people would call them racists. Some of them are, but in my experience, I’ve found that honest ignorance and a lack of interest in understanding different lived experiences are the real challenges they face, not outright racism.

Voting Republican —regardless of the candidate— is a given. Though they tend to be quiet about the specific politics of the day, the singular issue of abortion will unleash full-blown brutalization, with the concept of loving their neighbor being abandoned entirely.

Sometimes they dabble in far-right ideology and misinformation, but more often than not, they adhere to socially conservative media and worldviews. The hope that the Gospel offers each person is often confused with rugged American Individualism, causing the Gospel to be supplanted with a sustained culture war and nationalism.

Perhaps most importantly, they struggle to separate worshipping God with worshipping their church hierarchies and the belief that they hold the absolute truth, and wielding them against others.

Many absolutist white evangelicals also give generously. They serve others, sometimes as the most dedicated servants in a given church. They show up to many of the weekday events at their church, which are often far less attended than Sunday mornings. Many of them are genuinely nice and warm people, right up until one of the above issues arises.

The past few years, I’ve struggled to understand exactly who these specific white evangelicals are. On the rare occasion you can have a light-hearted conversation about evangelicalism with one of them, they will sometimes even laughingly claim that they confuse themselves. This tracks with their slight vacillations over time: hardened in so many of their views, they are still capable of empathy and being moved by human suffering.

It certainly is a far too easy trap to lay out a linear spectrum, dropping the love your neighbor evangelical and the raging political heretic on the ends, and the white evangelicals in the middle. The supposed better angels of evangelicalism often confuse the center with socially conservative policy, political independence, or worshipping the concept of having absolute truth on whatever issue —not the Gospel— and some don’t seem to understand that the Overton Window moving doesn’t always mean that Capital T Truth is getting sacrificed. This misunderstanding of the center is what gives space for absolutist white evangelicals to thrive in their hardness.

To be clear, most absolutist white evangelicals would never commit such a public act of violence as we just witnessed. In fact, many reject physical violence. That is a good thing.

Sadly, this type of white evangelical struggles to reject verbal and spiritual abuse, and they sometimes unknowingly incite it in return. After all, the term exvangelical exists for a reason: the American public is littered with people who have been chewed up and spit out by the darker side of white evangelical culture, often times for the most mundane of reasons, and far too often followed up with the haughty phrase “I’m just giving you the truth.” I know many exvangelicals. Some of their stories are absolutely gut-wrenching.

It is these two things: (1) the idolatrous worship of believing in supposed absolute truths on an issue alongside of or supplanting worshipping God and loving neighbors, (2) as well as confusing American Individualism and social conservatism with the Gospel, that has long contributed to the increasing polarization and the us vs. them mentality that surrounds all of us today.

Tack on a lack of curiosity in trying to understand the lived experiences of others and you are left with an insular culture that is dangerously susceptible to authoritarianism. And in this environment, the most dangerous impulses of white evangelical nationalism find individuals to pick off.

White Christian nationalism is part of what we saw at the U.S. Capitol on January 6. And many absolutist white evangelical churches are rich soil for this dangerous nationalism to take root in.

Absolutism and nationalism in evangelical culture are tied to at least four main problems

There have been many arguments made concerning where and when modern evangelicalism emerged, in hopes it can help explain today. Some point to the religious revivals of the 1730s. There’s the Second Great Awakening crowd. The Moral Majority crew. We could go on and on.

Contemporary evangelicalism undoubtedly has roots in many of these times and places. Studying the history of evangelicalism is certainly an enlightening activity, but the immediacy of the crisis in evangelicalism today requires us to look at the moment we are in with dispassionate clarity. When you do that, it becomes clear that this moment feels different, because it is different.

Problem 1: Evangelicalism has a leadership crisis at the local level.

I’m not talking about the likes of Eric Metaxas, Franklin Graham, and Robert Jeffress. In some ways, these well-known leaders of the religious right are distractions from a much deeper problem.

No, I’m talking about more run-of-the-mill leadership at the local church level. Incredibly kind pastors who really do mean well, but fail to understand the gravity of the political sorting in their congregations because their doors aren’t fully open to their members. Elders who hear shocking stories of right-wing political idolatry and its damaging effects in their church, but who decide to shy away from dealing with it out of fear of conflict, or becuase they quietly agree with it.

The type of leadership that confuses being right with doing right. The type of leadership that confuses preaching the Gospel with living the Gospel. And those are the good leaders. There are certainly plenty of abusive ones too.

Look, this is a crappy time to be a leader in the American Church. I am not a pastor nor an elder, but I do run a nonprofit that has a variety of Christians and non-Christians running around in our support base. The truly wonderful Christians who support us are exhausted by the last four years. Some of our non-Christian supporters have reached out to me for guidance on how to square up being friends to our Christian supporters with the darker side of white evangelicalism they see elsewhere in the world.

I’m not sure when this happened, but at some point the style of work pastors do creeped into my job description. I was sharing some of this with a pastor acquaintance earlier last year, seeking guidance for myself, and his laughing response was “Well, you understand what my life is like right now more than most other people do. Welcome to the club of terrible times.”

In times of crisis, we need perfection from our leaders, even though deep down we know they can’t give it to us. We should extend grace to them because of that reality. They’re going to make mistakes and come up short. I’ve come up short plenty of times the last few years.

At the same time, there is a fundamental issue here that is rarely talked about in white evangelicalism, isn’t there?

Many white evangelical leaders preach grace, and they preach it hard. But when it’s time for them to admit a mistake and apologize, crickets is often all we get. They’ll listen and even agree that a specific situation isn’t great, but their taking ownership becomes a step too far. Sometimes we even get verbal and spiritual abuse hurled back at us.

Much of white American evangelicalism is built around teaching grace, but when the rubber hits the road, there’s little of it to go around. The pastor’s door becomes a little less cracked open and elders shy away from dealing with political idolatry and conflict, leaving congregants feeling separated from their leaders. Nationalism and absolutist thinking thrive in this environment.

Problem 2: Teaching is often confused as leadership in evangelicalism.

Most pastors will tell you that their email inboxes have more combative messages from their congregation than ever before, messages like:

“This article about (insert issue) is a clincher.”

“I can’t believe you said that in your sermon on Sunday.”

“(Insert problem) is happening at our church. Why aren’t you doing anything about it?”

This sometimes sets off a chain reaction. If a problem gets loud enough, a sermon series is formulated. A few congregation members will inevitably be angry about what they hear, but some will find the series beneficial. Most probably won’t care.

And then nothing changes because teaching doesn’t translate into action by church leaders. Repeat cycle.

This happens for all kinds of reasons, and some of it has to do with how poorly churches are structured. But it often boils down to confusing teaching with leading. The pastor spoke on the issue, now it’s up to everyone else to live it. But that’s not how people work. If church leaders don’t exhibit the behavior being taught, the congregation definitely isn’t going to follow along.

White evangelical culture is full of this reality today. There’s way more talking than doing. Consuming parts of the Gospel that are being over-analyzed to death has become confused with living the Gospel.

For example, maybe we could learn more about living the Gospel if the pastor and elders of a white evangelical church that is up in arms about Black Lives Matter actually went to a BLM protest? Not because they are forcing themselves to agree with every little detail of the BLM platform. But to listen. To learn. To peacefully engage. To try to understand someone else’s lived experience.

Wouldn’t that be more Gospel-centered than using the Bible to urge a room full of white evangelicals to chill out? Isn’t that more Great Commission-oriented than trying to understand real world problems from the safety of an air-conditioned room?

Don’t get me wrong, teaching in Christianity is important. We’re blessed to live in a time in which there are more ways to access teaching than ever before. But blessings can become curses, and my sense is that an over-abundance of teaching has turned the Christian faith into a consumer culture for many white evangelicals. We can’t teach our way out of the world’s problems, nor will teaching alone reduce nationalism and absolutist thinking in white evangelical culture.

Problem 3: Evangelicals often confuse peacekeeping and peacemaking. Severe problems are not dealt with because of it.

There is genuine confusion around the difference between peacekeeping and peacemaking. This contributes to the absolutism and nationalism that are wreaking havoc in white evangelicalism and spilling over into our national politics.

Peacekeeping happens when a conflict can’t be resolved or so much damage has been done that leaders freeze the situation to keep it from getting worse. As they start to thaw the situation, leaders watchfully patrol to make sure it doesn’t start spiraling again.

Peacekeeping is a useful tool. It provides time and space for a heated environment to cool down, protects human life and dignity, or figures out exactly what the problem is in the first place. But if real peace is to be secured, something has to give. Something, or more likely someone, has to change.

And that’s the difference between peacekeeping and peacemaking.

Peacemaking is dealing with the actual problem head on. It’s the figuring out how to move forward part, and then actually doing it.

Peacemaking is hard. It often feels more hopeless before it gets better. Sometimes it involves recognizing that there isn’t a good solution, and the people involved should permanently go their separate ways or learn how to live together in disagreement. Wrongdoing can be so severe that it requires accountability.

And for these reasons, it’s why peacemaking is so rarely pursued in white evangelical culture. Conflict and accountability stinks. Dealing with difficult problems isn’t fun. But they are inevitable parts of peacemaking.

Ask just about any absolutist white evangelical what they want today, and peace is normally near the top of their list. Why can’t we just have peace? is a common, frustrated question in white evangelical culture. Oddly enough, I very rarely hear the question How do we get to a more peaceful place?

This isn’t a problem unique to white evangelicals. It’s really just a human problem. The one difference for Christians is Jesus, who says in Matthew 5:9:

“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God.”

Many of us probably wish Jesus had said Blessed are the peacekeepers. That would be so much easier. No, Jesus says do the hard thing. Deal with the problem. Make the peace.

White evangelical culture is trapped in cycles of peacekeeping, or just ignoring real problems. It rarely gets to the next step. And in today’s climate of conspiracy theories, misinformation, far-right ideology, and political idolatry, that’s really bad. Many white evangelicals extend their belief that they have absolute truth to every issue. When it comes into conflict with others operating the same way, but with a different view, boom. It’s us vs. them. Conflict ensues. Others step in to keep the peace, or more commonly, one side just permanently walks away in frustration.

No one has to soften their views, nor embrace the reality that they are human and can’t possibly know everything. No one is forced to see the person on the other side of the issue from them. The problem isn’t resolved, and people can’t learn how to respectfully interact with those who see the world differently than they do, often with good reason. This is fertile ground for nationalism, because it makes it way too easy for people to harden into absolutist positions.

Justice is what leads to peace. Human justice will always be flawed, but at the center of it is being able to see other people as human beings. The best institutions place human flourishing at the heart of their mission, just like the best friendships help each other flourish. Disagreements always have to be secondary to seeing the human being across from you. White evangelicals claim to believe that every person is made in the image of God (Genesis 1:27). Sadly, many do not live that belief.

Problem 4: Evangelical culture is increasingly entitled and insular, exactly when our country needs the American Church to humbly live the Gospel more than at any other point in our lifetimes.

There is no doubt that the world is a scary place right now. In the midst of a raging pandemic, it is easier than ever before to shrink into our own homes, our own beliefs, and our own prejudices.

Nowhere else in American life is this circling of the wagons occurring faster than inside of white evangelical culture. At a time when churches should be throwing the doors to their resources open, they are slammed shut. Deep inside, white evangelicals are becoming more embittered by their entitlement, as well as more fearful in their failure to engage with the world:

“The world hates us.”

“This is a Christian country and we have to fight to keep it that way.”

“The socialists are taking away our right to worship. We need to resist and fight for our religious liberty.”

Those are real quotes I’ve heard from white evangelicals, just in the past few weeks. They are inherently anti-Great Commission statements.

Jesus never said go to where it is safe or where everyone agrees with you. When he gave the Great Commission (Matthew 28:16–20), he said go to all nations. Period. No room for exceptions. And we know from his ministry that includes listening to others, meeting physical needs, and gently sharing our faith.

The increasing insularity of white American evangelicalism is built around a culture of entitlement, absolutism, and nationalism. It makes the Church an unwelcoming and unloving place.

Yes, white evangelical, the world is changing. The Church is becoming more countercultural. And that is mostly your fault.

No, white evangelical, you are not being persecuted. You are not entitled to live in a Christian country. And if you chilled out long enough to really examine your surroundings, you’d be surprised to learn that there are political socialists across the American Church, and they are doing the Lord’s work in some breathtaking ways, often times alongside of people who are conservative, liberal, and moderate.

Insularity is anti-Gospel. One of the many things our country needs right now is a church culture that humbly serves and struggles toward peace. At the local level, many white evangelical pastors often proclaim this, boldly declaring that only the Church can deliver the peace our country needs.

There’s just one problem: the insularity of evangelical culture is preventing the Church from showing up in the way our country needs.

Right now, many church leaders are urging their congregants to come to Sunday morning activities — despite the very real public health risks large gatherings pose — because the need for community is real. Let’s be frank though: the country doesn’t need white evangelicals hunkered down in their churches right now, wringing their hands over the culture wars and self-circulating a virus. The world needs Christians out in the broader community, quietly serving those in need as safely as possible, and helping to make peace in a society that is coming apart at the seams.

To be fair, there are a lot of Christians doing this. I know quite a few of them, and I am right there with them. But many of us will tell you that too few institutional churches are backing us up. Many feel like they are being shot in the back by their own team.

Removing this culture of entitlement, absolutism, and nationalism in white evangelicalism won’t happen overnight. But it can be minimized now by evangelicals purposefully walking out of their safe havens and putting themselves in proximity to others who don’t look like, think like, or believe like them. It’s called the Great Commission, and there has never been a better time to live it in our lifetimes.

Closing Thoughts

White evangelical culture has become the epicenter of what many church leaders have long warned is coming: a post-truth world. White evangelicals arrived at this point by placing the idolatrous worship of flawed “absolute” truths they created, based in social conservatism, and wielding them against others above loving God and loving our neighbors. This became fertile ground for the hardness of political idolatry and misinformation to thrive, and nationalism soon followed.

It didn’t happen overnight. In many ways, Trumpist evangelicalism is just the latest iteration of the wrapping of the American flag around the cross of Christ. It’s not a new phenomena, but it is a predictable one with predictable outcomes. White evangelicalism is a cultural experience, not a Kingdom one. And it’s become a breeding ground for violent insurrection.

As predictable as white evangelical participation in the insurrection was, there is something different this time, isn’t there?

The damage that was done to the American Church and the Gospel will last for at least a generation, if not longer. In a single day, white evangelicals went from being the laughingstock of the country — due to four years of the rank hypocrisy found in their unholy marriage to Donald Trump and vile Republicanism — to being seen as a dangerous threat to the Republic.

There is no quick fix to the catastrophic damage that was just done. A public relations blitz won’t be enough to get white evangelicals out of this particular mess.

Just like our democracy, white evangelicalism is long overdue for top to bottom reform. Sadly, reform appears to be nearly impossible in the current white evangelical subculture, which is prone to knee-jerk, negative reactions at the mere mention of change. The exodus out of white evangelicalism was well underway before this moment. It’s not hard to imagine that exodus is about to drastically ramp up.

This begs the question that white evangelicals have long avoided, but direly need to answer: why keep fighting a losing and increasingly dangerous culture war when the Gospel is still available to you? When your culture war is causing violent extremists to emerge from your ranks?

Rarely in history has choosing the Gospel been the easier road to go down, but somehow it’s the easier road now. The answer to this question is obvious for so many reasons: choose the Gospel. Love the fullness of the God of Scripture. Love your neighbor.

Sadly, in many white evangelical bubbles, this answer is not so obvious. Warped by false beliefs of persecution, apocalyptic Republican fear tactics, and misinformation, white evangelicalism is probably too far gone to be salvaged.

If that ends up bearing out, white American evangelicalism will continue to die a slow, painful death. The casualties will extend far beyond the doors of their churches because, in times of total warfare, mass collateral damage is inevitable. One only needs to look at the latest culture war over masks, lockdowns, and vaccines to understand that the body count is already stacking up.

For those who believe white evangelicalism can change for the better — transforming into a more loving enterprise that is closer to who Jesus is — your struggle goes well beyond being an uphill one.

The landscape in front of you resembles the stormy Normandy coastline on June 6, 1944. The cliffs are teeming with the heavily-armed combatants of the white evangelical cultural wars. Wealthy, consumed by ideology, and with so much power to lose, they fully believe their absolutism and nationalism are righteous. Because of that, they eagerly pull the trigger, including against those in their own ranks.

Reconciliation without grace and repentance is not possible, and today’s white evangelical subculture is rife with anti-grace and anti-repentance stances. Even in peacetime, repair is a laborious, back-breaking work. And we are not in peacetime.

Simply put, it is not possible to storm the beaches of white evangelical culture. If only it were that easy.

Thankfully, you have reason to hope. Jesus spent his life here on Earth showing people through word and action that there is a better way. He is the ultimate peacemaker. His way must be your way.

So, love your neighbor. Serve the needy. Aid the poor. Safeguard the oppressed. Live the real Gospel by listening to those who have a different lived experience than your own, and the twisted absolutism and nationalism that threaten to tear parts of the Church apart will start to weaken, ever so slightly. And yes, serve those who have been damaged by white evangelicalism, including the exvangelical, who is so often ridiculed in evangelical culture.

You will have no Victory Day. You won’t even have a D-Day. This war can only be won with the relentless and radical example given to us by Christ. It is a strategy of persuasion through action.

You must do the work of the Gospel on the beaches, even as the loaded guns of absolutism and nationalism are aimed at you from the high ground on the cliffs above. Only there can you persuade those white evangelicals to lay down their ideological weapons, embracing the words of Isaiah in chapter 2 verse 4:

He will judge between the nations

and will settle disputes for many peoples.

They will beat their swords into plowshares

and their spears into pruning hooks.

Nation will not take up sword against nation,

nor will they train for war anymore.

This is what your fight will be. Most days it will feel hopeless, minuscule in comparison to the amount of change needed. Rejoice in the suffering that no doubt awaits you, and maybe, just maybe, a narrow path out of the darkness will emerge.

I explore faith, church culture, and formation in the American South from my hometown of Memphis, TN. I’m an institutionalist who believes the means are just as important as the ends. Everything on this site is an expression of my faith and love for the Church.

Never miss an article by signing up for my newsletter and subscribing to the podcast. You can also become a member or leave a tip to help keep everything free and open to all.